Building a shared brain for customer knowledge with Atlassian’s Sherif Mansour

Portrait of Sherif Mansour by Tia Alisha

“If you’re in your 30s or 40s, generationally speaking, you probably fell into product management.”

This is a story Sherif Mansour, Distinguished Product Manager at Atlassian, loves to tell.

It’s a common refrain among the industry’s senior PM cohort. More than ten years ago, when Mansour started his professional journey, the role had barely left its adolescence, and there was little to nothing to speak of in the realm of official product management qualifications.

From graduate engineer (“I was a terrible engineer,” he says) to the inimitably titled “Distinguished Product Manager” at one of the world’s most innovative software companies, Mansour’s career almost perfectly parallels the rise of product management from relative obscurity to a role that’s been referred to as the CEO of product.

To put this in perspective, Mansour’s first foray into the profession landed him on Atlassian’s Confluence team back when it had 15 people on board. “There was a part-time designer. And so I was in design for half the time. And that was it. But we had no researchers. We had no analysts,” says Mansour.

Now, with the rise of specialist designers, researchers, and analysts, and an ever-growing subset of specialties emerging each year, the role of product manager has changed, but according to Mansour, the core principle — to solve customer problems — remains the same.

What makes a great product manager?

For a role as central to the product development process as a product manager, the term still has a nebulous feel. It’s strange to think that out of the billions of customers worldwide receiving new products and features every year, most of them probably don’t know anything about the people who make it happen. According to Mansour:

A product manager is the person who identifies the customer need and the broader business objectives that a product or feature will fulfill, articulates what success looks like for a product, and rallies a team to turn that vision into a reality.

To put it simply — a product manager spends their days trying to understand what customers want and then figuring out ways to give it to them.

But if it still feels vague, that’s because the role is so varied in scope and scale, single definitions rarely capture the whole concept. A product manager has a broad set of responsibilities and several different tools at their disposal for problem-solving, meaning on the individual level and organizational level, styles and approaches vary, often significantly.

For example, the question, what makes a great product manager, yields a multivariate response from the Atlassian veteran. “It depends on the context of the organization and what they’re trying to do,” he says. “In a startup, you might not be necessarily looking for a product manager that can lead because you’ve got a founder, but you’re looking for someone who can execute.”

“In that case, you’re looking at taking a blurry vision from someone else and trying to define it, trying to validate it and doing research to convince the startup at the time that this is the right direction.”

On the other hand, in larger organizations, Mansour explains, product managers put more time into “navigating the organizational landscape to get an outcome” — that is, getting buy-in from leadership, as well as stakeholders — all while focusing on the market landscape to ensure the viability of the business.

Creating a shared brain

SafetyCulture

The product team at SafetyCulture built a centralized research repository with Dovetail.

Learn how they did it

According to Mansour, at the highest level, the product manager provides three robust solutions for their team:

- Fostering empathy by centering the customer and their needs.

- Speeding up decision making, so the team works more productively and cohesively.

- Owning the roadmap for product development and helping their teams understand what problems they are solving, when, and why.

“Traditionally, most organizations say a PM owns a roadmap, a spec, and a backlog,” says Mansour. “What is a roadmap, a spec, and a backlog? They’re all solutions. What problems are those artifacts trying to solve when you go back?”

“[The roadmap, spec, and backlog] try to give you a shared context of the high-level vision and how you’ll go about executing it. They give you some context on what problem you want to solve and how you’ll be able to deliver value to customers incrementally.”

Mansour calls it “creating a shared brain,” and it’s the product manager’s full-time responsibility. From influencing teams without authority to getting decisions made and shipping products, it all relies on the product manager’s ability to get the whole team on the same page.

Sherif Mansour, Distinguished Product Manager at Atlassian

The rise of specialists

The days where Mansour worked on small engineering teams with part-time designers and no analysts or researchers are over. As the market demands higher quality, customer-centric products, specialists of all shades and colors have emerged to take on the challenge.

Product managers were once the fount of all customer knowledge. When it came to design thinking or customer research, they were keenly connected to the market, and were often the most ardent advocate for the end-user.

But with a rise in specialist researchers, analysts, and designers, often all with their own sub-specialties, is the product manager’s role being eroded? Is there a rising tide of tension developing between the different decision-makers, all of whom claim to be the voice of the customer to some extent?

The rise of specialists [like researchers] often creates anxiety, I guess, and a bit of tension for product managers, because some of them say, ‘I was talking to customers, now I have a researcher. What do they do? I was the person doing UX validation testing. Now, what does my full-time designer do?

Collaboration is key

As research and design specialists join the fray, a PM doesn’t risk seeing their contributions diminished, but rather they may fall into a trap where they become akin to a project manager, supervising the handover of various tasks from one specialist to another.

“What I tell people to do is to conduct the discovery process (learning what is it we’re trying to solve and how might we solve it) as a shared working group, not a set of individuals,” says the seasoned PM.

“The anti-pattern is to take your specialist researcher, and you tell them to do their job and produce an artifact for that role.” Instead, what works better, according to Mansour, is specialists democratizing their knowledge.

The real specialists that shine are the ones that say, how do I make a researcher out of everyone? Or the UX specialist says, how do I make a UXR out of everyone? Not because someone could get trained in research overnight and have a Ph.D., but because they realize it’s the best way they can influence others and add value to the table.

So, where does this leave the product manager? In Mansour’s opinion, a good product manager can’t simply be a generalist, nor should they fall into a project manager role where they oversee the handover of various specialist functions in the product development process.

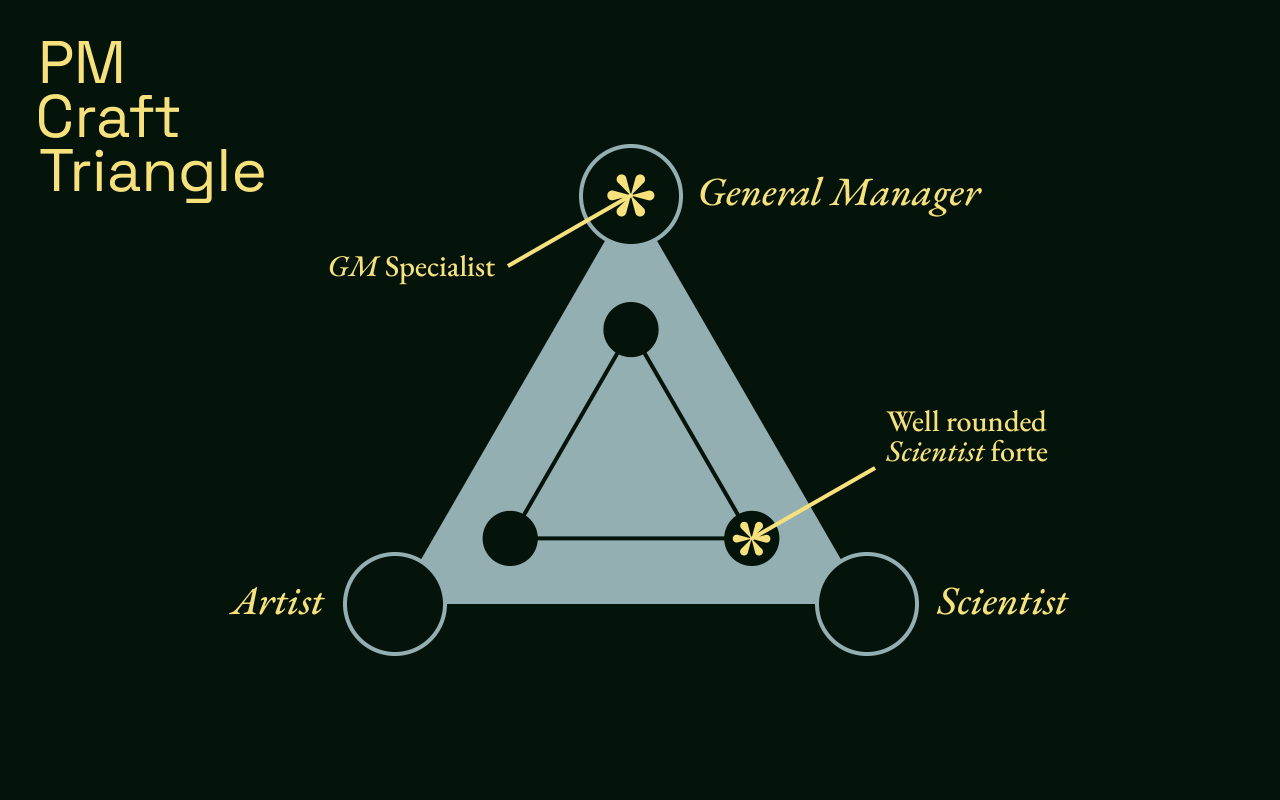

“I would say that good product managers have one leg of the stool that they know well.” Mansour refers to an idea called the ‘PM Craft triangle’ (a term coined by the current VP of Product at Atlassian, Joff Redfern). The concept is that product managers are a mix of artist, scientist, and general manager, with one corner of that triangle usually preferred to others. “In my experience, I haven’t met many great PMs that are in the middle,” states Mansour.

PM Craft Triangle by Joff Redfern

“When I form a team, I’m very conscious of the kind of PM I need for the work and how I can complement their skillset,” says Mansour. “If you put three people that think alike in a room, of course, there’s going to be overlapping skills and confusion as to who does what. I think what that helps us do is build a more deliberate team formation. It’s about a balanced view where we make sure we complement each other.”

The future of product management

Toward the end of our conversation, we talk about the increasing number of sub-specialties within design, engineering, and research. The question is, will product managers, or should product managers go in the same direction.

Specialization might take the form of the PM triangle made explicit in role titles. A strong data analyst would differ from a business- or UX-oriented product manager, and the titles they hold could reflect those strengths. While Mansour acknowledges it would make it easier for hiring purposes, he’s cautious about endorsing the concept.

“I don’t know if that’s good for our discipline as a whole, because we start to encourage an insular view of what the job is trying to do, which is really to be a shepherd for our customer problem,” says Mansour. “Those job titles are how I approach solutions to those problems.”

“Maybe it’s the purist in me at the end of the day, but the exceptional product managers are those that fall in love with the problem space and do everything they can to improve that problem space.”

“I think we want to motivate the discipline to focus on that rather than start with a specialist solution in mind.”

Subscribe to Outlier

Juicy, inspiring content for product-obsessed people. Brought to you by Dovetail.