Continuous Discovery Habits with Teresa Torres

The product coach.

Published

22 November 2022

Content

Creative

The author, thought leader, and product coach waxes lyrical on the value of talking to more customers, more often.

Teresa Torres immediately strikes you as a coach—in the traditional sporting sense. She’s passionate, vivacious, and brimming with enough energy to power a small village. Her voice is a little hoarse, giving the impression she’s recently been shouting from the sidelines of a basketball court. A tendency to speak her mind and a no-bullshit attitude conjure images of pep talks and rousing half-time speeches.

It’s an image she carries well. And as someone who’s been on the frontline of product development for decades, Torres is well worth listening to. Particularly when she’s dropping 50-megaton truth bombs.

“When I hear product managers say they don’t have time to do research, what I hear is ‘I don’t care enough about building a product that matters,’” Torres opines. “I know that’s not what people mean when they say that, but that’s the reality. If you can’t find 30 minutes a week to talk to a customer, how in the world are you going to build something that meets that customer’s needs?”

In case you can’t tell, Torres feels strongly about research. So much so that she’s dedicated her career and an entire book, Continuous Discovery Habits, to the subject.

The book, which has been lauded by product leaders like Marty Cagan, is fast becoming a mainstay on the bookshelves of PMs worldwide. It’s easy to see why. Torres covers an immense territory in a short span, instructing her audience in an easy-to-follow, tactical way, helping them achieve a continuous cadence of discovery work.

In our hour-long conversation, we dig down into the details of Continuous Discovery Habits, talk product team best practices, explore experience maps, and the product management veteran predicts the future of the discipline.

Becoming the coach

Before becoming what was likely the first Product Discovery Coach, Torres had a varied career. She began as a designer—or as she puts it—“a front-end engineer with a human-centered background,” working for “companies that don’t really care about design.”

It was the early days of digital products, and like many in her cohort, she stumbled into product management. “Eventually, I worked at a company with a VP of Product, and when I started working there, he was like, ‘You’re not a front-end engineer or a designer. You’re actually a product manager.’ And I was like, ‘Okay, that sounds cool, let’s do that.’”

It wasn’t long before Torres found herself leading teams and even entire organizations, going from VP of Product to a stint as CEO. “I didn’t love being an executive,” she confides.

Tired of working at “founder-led” start-ups where she would have to fight for customer-driven decision-making, Torres quit the executive life and took on a new mantle as a Product Discovery Coach. “I had this core belief,” she tells me.

“If you talk to your customers, you will build better products. I want to figure out how to help teams talk to their customers more.”

Stretch goals.

Why discovery matters

“Discovery is just the work we do to decide what to build. Every product team on earth is doing discovery.” Torres explains why she chose to focus on this particular part of the product development cycle. In typical Torres style, she provides a lot of detail quickly. “Now, actually, that’s not true because sometimes their stakeholders are doing discovery and telling them what to build,” she adds caustically.

If all teams are doing discovery and it's an ongoing, iterative process, then the idea of continuously involving customers is a no-brainer. This is the thesis of Continuous Discovery Habits and the core mission of Torres’ professional life.

The notion that product teams should regularly connect with customers is straightforward. But that’s not the way the world works. Even though the product community broadly supports customer-led product development, where agile teams make autonomous decisions about what to build next based on research and insights, most businesses still struggle to execute this operating model.

As to why, Torres blames the internet. “Before the internet, waterfall and business stakeholders deciding what to build worked just fine,” she says. “It worked because you didn’t have to build the best product. You had to get on store shelves and have a better position than your competitor, right? So the biggest differentiator was distribution. It wasn’t the quality of your product.” Torres says the internet evened the playing field for distribution, and product quality became much more important. Greater access to information also gave consumers more power over their choices, and it became harder to force bad solutions on people who knew full well there were better alternatives.

Most product managers aren’t product managers

Businesses change at a “glacially slow pace,” says Torres. Most still operate on a “Taylorism” philosophy of efficient assembly lines. This is why she argues that “probably 90 plus percent” of product managers aren’t actually product managers.

Instead of innovating, connecting products to marketable solutions, and driving development in a customer-centric direction, most product managers are “cranking widgets on this assembly line.” Essentially, most product managers are operating on a day-to-day level as project managers. Without consistent, strategic connections with customers—without a continuous discovery motion, where PMs uncover, evaluate, plan, and market new solutions, Torres is arguing that it’s hard to call what most PMs do real product management.

It’s a common complaint echoed throughout product management communities across the internet. But there’s hope—many of the world’s most successful companies are working in a new way that leads to better outcomes. While Torres says that ditching your old company and finding a new one is always an option, she’s also bullish on simply changing the way you work as an individual.

Screw buy-in, do it anyway

The obvious first step to ditching the widget-cranking life and becoming a bona fide product manager is to talk to customers regularly. And if you work at an organization that makes this difficult, do it anyway. “I’m probably a single degree away from somebody who’s my customer. So why do I need permission? Whose buy-in do I need?” asks Torres.

The product coach argues that you can always find someone to speak to. And once you’ve had those conversations, you should ensure the value is known across the organization.

Suppose you work with customer-facing teams who aren’t always comfortable with you speaking to their contacts. In that case, Torres says to ask to sit in on a few conversations, get them comfortable with the idea, and show your skeptical co-workers you’re not going to do any damage. “When they’re comfortable with that, maybe the next thing you do is you ask if you can ask a question at the very end of the conversation and maybe even tell your colleague ahead of time what you’re gonna ask so that it’s not scary,” she says.

Do it regularly

“Start by talking to one customer a week,” says Torres. And if that sounds like a lot, get there continuously. “You can get to one a month and then one every three weeks and then one every two weeks and eventually one a week. For some teams, that’s going to be adequate, right?”

If you work at a company that releases slowly, that should be enough. If you release more regularly, you should look at upping the cadence. “I have worked with teams that talk to customers every single day. I have talked to customers every single day. I have worked with plenty of teams where I would say do not talk to a customer every day because you’re going to be overwhelmed with data, your delivery process doesn’t work fast enough to support that, and you’re just wasting energy. So I think it’s really important the feedback cycle matches your delivery cadence,” she tells me.

Keep it small

At the beginning of this piece, I dropped a polarizing Torres take. To paraphrase: if you don’t have time to talk to customers, you don’t care about making a product that matters. It’s harsh but fair. But Torres has the answer for the average time-poor Product Manager—don’t make research a big deal.

“The time thing, it’s really about project-based research,” says Torres, referring to the traditional approach to research planning. “We don’t have time to do project-based research. A product team does not have time to talk to 12 customers in a week. They don’t. There are too many other things that they need to do as part of their job. So I think a lot of that comes from this old model of project-based research and getting buy-in and being allowed and finding time,” opines the product coach.

“When we adopt a continuous cadence, all of those things go away. Everybody has 30 minutes they can fit on their calendar,” she says.

Build your knowledge. Make it shareable

Continuous Discovery Habits is full of tips, tricks, frameworks, templates, models, and more for getting better at discovery and making great products. You really should read it. It’s impossible to summarize all the fantastic work Torres has done in the space of the 200-odd pages of Discovery Habits here. But I’d like to zoom in on one particular exercise she recommends—the experience map.

An experience map is a visual representation of what you and your team already know about the customer and their problems. Before doing any research, make that explicit. Have each team member provide their unique perspective on the customer problem you’re working on. It’s important that everyone completes this individually to avoid groupthink and that the scope is limited to a specific outcome you’re looking to pursue.

An experience map can help align the team around the customer problem. “A lot of team disagreement comes from the fact that I know some stuff, and you know different stuff. We’re not sharing that, so we’re drawing different conclusions,” says Torres.

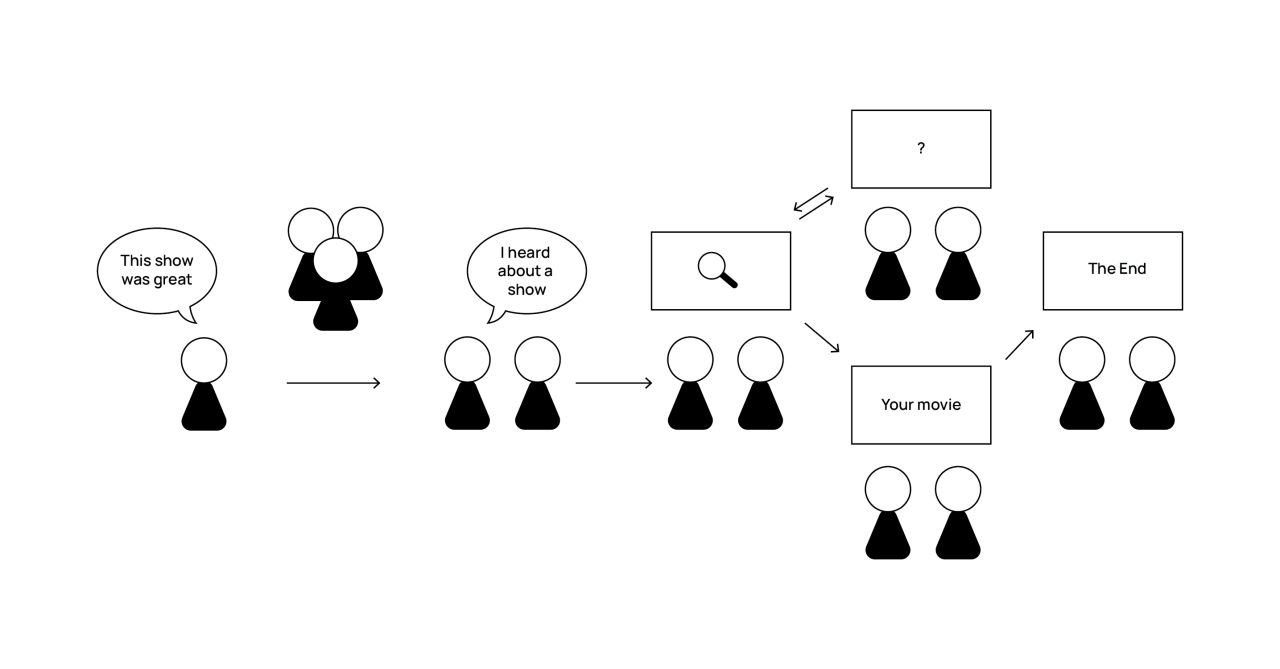

Once everyone has completed their map, compare and contrast. Don’t look for “wrong” or “right.” Instead, be curious, focus on the differences between each map and try to understand how each team member has understood the problem. Once you’re done, synthesize everyone’s maps by turning each aspect into “nodes” and “links.” A node is a specific moment in time, and links join nodes. Include everything from all your team’s maps, collapsing similar nodes. Remember: don’t just add the “happy path.” Capture steps that have to be redone, where people might give up out of frustration, or where steps might loop back on themselves. Finally, add context to your map for each step. What was the customer feeling, thinking, and doing at each step of the journey?

An example experience map for finding content on a streaming service. Courtesy of Continuous Discovery Habits by Teresa Torres.

Once you have a fully synthesized experience map, you have something to test when you go and talk to customers. “It’s this living document that allows you to capture what you think you know about your customer. Because we’re explicit about that, every interview we run can test it. We can evolve it and iterate on it,” says Torres.

The best product teams

According to Torres, there’s no such thing as the perfect team. There are many ways to do it well, and some core principles she looks for. Here’s an at-a-glance look at the high-level principles you should strive for in your product team.

- Is your team truly cross-functional? “Do we have product manager, designer, software engineer, and other roles collaborating on what they’re building? Not just with handoffs or passing the buck down the line?”

- Are you engaging with your customer? “How good are your feedback loops? How often is your team engaging with customers?”

- Are you working sustainably? “I would rather a team talk to one customer weekly and have sustainability, which is why I talk a lot about habits.”

- Do you know anything about reliability and validity? “We’re not expert researchers; we don’t need to be expert researchers. But we need to know a little about the concepts of reliability, validity, and research. How do I know what a participant tells me in an interview matches their behavior? How do I know if I interview someone tomorrow, they’ll tell me the same thing? How do I know if I run an assumption test, the way that a customer interacts with my prototype is the way they’ll interact with the product?”

The future of Product

I asked Torres to grab the crystal ball, and tell us what the future has in store for the product world.

True to form, she gave me the most down-to-earth answer I’ve heard. “I think for most of us that are alive right now, for the rest of our lives, we’re gonna be getting good at the existing stuff,” she tells me. “And I don’t mean that the existing stuff is the endpoint and the be-all-end-all, but it’s going to take so long to get good at this stuff. In broad strokes, I think 50 years from now, we’re still going to be looking at how to engage with our customers more often. How do we get more reliable feedback from them? How do we build iteratively so we don’t build too much? I don’t think those things are going away,” she says before adding, “Humans change too slowly.”

Although this sounds like a dim view of the future, somehow Torres sounds optimistic when she says it. Like a true coach, what excites her most about the future is perfecting our fundamentals, getting good at the basics. And rather than getting frustrated by the glacial pace of change, it invigorates Torres, inspiring her to pull up her sleeves, take action, and get to work.

She leaves me with a final bit of continuous discovery wisdom: “If we can see that we’re getting better and if we assume we keep getting better, then 50 years from now will be better than we are now, and that’s good enough for me. That’s the value of continuous improvement. I don’t have to worry about five years from now. I just have to worry whether next week looks a little better than last week.”

Subscribe to Outlier

Juicy, inspiring content for product-obsessed people. Brought to you by Dovetail.