What I learned setting up a research practice at a fast-growing B2B company

The world of B2B.

Published

22 January 2023

Content

Creative

Collaboration, budget, and tooling—plus extra tips for getting a research function off the ground.

If you’ve been the first researcher at a company, you know: It’s an incredible honor to set up a practice from scratch.

It’s also, to put it mildly, a challenge.

And if you’re setting up a research practice in a B2B environment, there are all sorts of added challenges: Who, exactly, are the users? Are the users customers? What about the users who aren’t customers? It’s enough to make your head spin.

I got my first introduction to the world of B2B nine years ago in a university class I taught. We paired students with a large B2B enterprise company and challenged the students to create a social media marketing campaign for them.

The students had a lot of questions. What exactly was B2B? To whom were we supposed to market the products: The companies that bought the products? Or the end consumers who used the products? No one seemed able to answer this question, including the company themselves. It was a confusing time, and I told myself I would avoid B2B work in the future.

Fast forward six years, my first UX research role was to lead the practice at a B2B company, which—similar to that giant enterprise company—was somewhat confused about who their users were. They also had a 400-plus workforce and had never worked with researchers before.

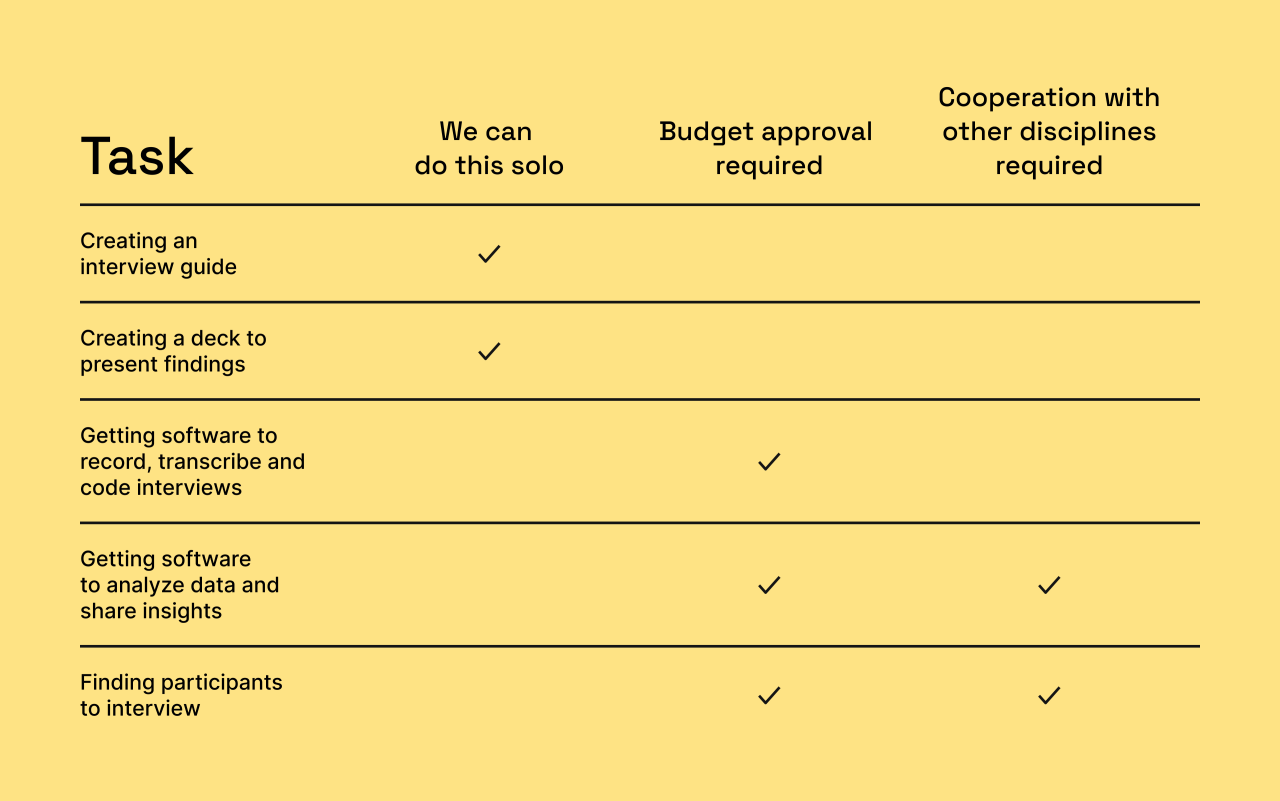

That’s setting the stage. Now let’s talk about what happens after you’ve got the job and started your first research project. That moment when you realize you have to actually conduct research. And the practicalities start creeping in. Tasks and challenges emerge, like:

- Creating an interview guide

- Building a deck to present findings

- Getting software to record, transcribe, and code interviews

- Getting software to analyze data and share insights

- Finding participants to interview

This process of actually conducting a research project led to my first lesson:

Lesson one: We’re going to need a system to make all this research happen

In retrospect, it sounds so obvious. But it wasn’t a task I had envisioned for myself. I had imagined my first UX research role in an established company would entail churning out usability tests for a couple of years until I earned my stripes.

Since then, I’ve learned that despite all the press and attention FAANG/MAMAA companies get in the UX research community, most organizations aren’t high in research maturity. A lot are just starting.

If they’ve never done research, they certainly won’t have systems to facilitate it.

Creating a system wasn’t just about running through the checklist above. Because research projects were—in the best-case scenario—going to be set on repeat. As our team grew, we could bring more and more insights to the table. We couldn’t possibly do all of this ad hoc.

So we created a checklist of what we would need, from proper consent forms to best practices for insights sharing. We created a file system to keep our materials organized and accessible to others. We crafted research project artifacts like consent forms and interview guide templates.

These were things that we could do solo. But we quickly realized: there were many things we couldn’t do alone. In some cases, we needed budget approval from our manager or other budget holders, and some tasks required cooperation with other people at the company. That led me to lesson number two.

Lesson two: Our operational structure should not and cannot grow in isolation from the rest of the company

Successful researchers cannot work alone—that was clear. But it was more than simply introducing ourselves to others or “getting to know” our colleagues. Two things became quickly apparent:

We would need money

We would need to build well-functioning, productive relationships and collaborations.

We’ll come back to budget in lesson three. First, let’s talk about collaboration. To succeed, research needs more than skilled researchers. It requires fruitful cross-disciplinary cooperation. I’m not only talking about the obvious collaborators like designers, data analysts, or product managers. The collaboration I’m thinking about must take place with people in teams you probably haven’t even met yet: sales, marketing, and the all-important Customer Success Managers.

No researcher is an island.

Why CSMs? I have three words for you: Research participant recruitment.

It didn’t take long to realize: CSMs would need to become our BFFs. If not our BFFs, at least enthusiastic enough about our work to share the potential value with their customers.

CSMs are experts on individual customers—in the B2B case, they know particular companies’ pain points and needs inside and out. From the researcher’s perspective, because CSMs know these customers so well, they are often the best bet to connect customers with user researchers.

Remember all that confusion about customers and who actually uses the product? CSMs have a lot of insight into this process. Because they’ve built close relationships with customers, they have, in a sense, been conducting ethnographic case study research for as long as they’ve worked with that particular customer.

Once we figured this out and built these important relationships, things started running smoothly. But if a UX research job has taught me anything, the learning never stops. That leads me to Lesson number three:

Lesson three: Getting buy-in for research operations isn’t the same as getting buy-in for researchers.

Getting buy-in to expand your research team, as in hiring expert researchers, is a massive exercise in stakeholder management. I’ve written several articles on this topic, for example, about honoring the non-research perspective or approaching research in a low-maturity organization. It’s essential, especially as demand for research increases, that you grow your capacity to conduct and provide expert support for your company’s research needs.

However: Those same individuals you need to approach and convince to open up headcount for their “own” researcher or a researcher who will support a product or topic close to their heart may not be as keen to financially support an operational budget that serves the entire company.

My advice? Figure out who holds the purse strings. It might be your manager, your manager’s manager, or someone else. Find out who this is and what they best respond to. Learn about the history of approvals, especially for new functions like research. If it’s your manager’s manager, don’t go over your manager’s head and talk to this person. Work together to come up with the best approach.

Once you’ve gotten that first, all-important approval—maybe a subscription to a platform for qualitative analysis or a digital diary study tool—it’s time to sing their praises. Praise this person when you’re demonstrating how much smoother your research projects are running, thanks to their generous support. Everyone likes to be the hero, even if it’s just signing approval for something as mundane as AI interview transcription software.

But let’s take a step back. Even with that person’s approval, it’s not necessarily smooth. In my experience, it wasn’t because the budget holder was unwilling to provide us with the tools necessary to build a thriving practice—although that could be your situation.

The problem came in procurement. Imagine signing up for an enterprise account with a research repository platform. You check the box, and they give you unlimited access. You send the bill to your procurement department and assume it’s being taken care of. In the meantime, you’re onboarding researchers and learning how to use the tool. You’re storing interview transcripts and analyzing the results. Then, one day, the lights go off—no more access.

It turned out our procurement department didn’t honor 30-day payment periods, only 90-day. Time went on, and they don’t honor 90-day periods, either. It could happen to you, too: the platform you’ve signed up for—rightly so—has gotten fed up with not getting paid and has cut you off.

My advice? Make it an early priority to sort out what you’ll need to get your research operations up and running. Especially from a tooling perspective, get those requests in after you’ve built that all-important budget-approving relationship. Depending on your company, it could take months until you’re able to utilize these investments.

Being the first researcher at any company is a huge, exciting, and humbling experience. You’ll laugh, cry, and learn a ton along the way. Although it’s a lot of work, watching your efforts slowly transform a company’s mindset toward research insights will make it all worthwhile.

Subscribe to Outlier

Juicy, inspiring content for product-obsessed people. Brought to you by Dovetail.