The impact of behavioral science on market research and consumer insights: from ‘Nudge’ to ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow,’ and beyond

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Traditional market research tends to have, as its starting point, consumers making choices based on a rational weighing-up of information they have to hand. Think ‘Homo economicus,’ the theoretical abstraction that some economists use to describe a rational, self-interested human being.

However, the popularization of behavioral science, with its roots in psychology and economics, has revolutionized how we analyze and interpret consumer behavior.

This article explores the profound influence of behavioral science on market research and consumer insights, examining the Nobel Prize-winning contributions of Richard Thaler in the field of behavioral economics and Daniel Kahneman, recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics. Thaler's revolutionary book Thinking, Fast and Slow and Kahneman's work Nudge are testaments to their impact.

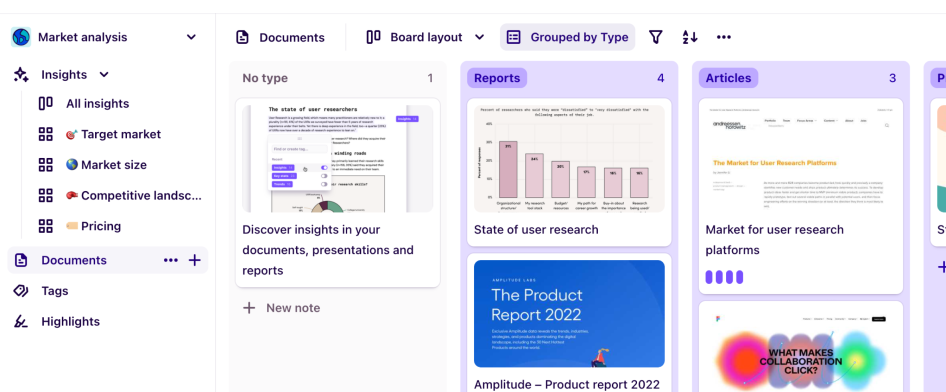

Market analysis template

Save time, highlight crucial insights, and drive strategic decision-making

Use template

The emergence of ‘nudges’ and ‘interventions.’

I remember the arrival of ‘nudges’ and ‘interventions’ when behavioral economics and behavioral science were first discussed in market research.

Nudge, published in 2008, initially caused a stir: I was in the UK and recall hearing about the ‘Nudge Unit’ (“Good name for a band!” I thought). In 2010 the Cameron Government set up this behavioral insights unit to embed behavioral science principles in policy and governance.

It was about this time that the market research agency I worked for hired a Ph.D. in behavioral science, and we started investigating how we might build their expertise and thinking into how we conducted and delivered our market research.

However, the behavioral science wave truly broke with the publication of Thinking, Fast and Slow.

It became embedded in business language and thinking (and certainly part of market research). I remember seeing its distinctive white cover everywhere, with the yellow pencil on the front, and yes, I bought myself a copy.

Interestingly, a book as influential as this one is only finished by a mere 7% of readers (according to a rough analysis of Big Data). I felt seen as I bought it and certainly enjoyed it, but about three-quarters of the way through, I thought I got the point and never finished it.

Part of the reason I didn’t finish it was:

a) It was 499 pages long. When I bought the book, I had a 9-month-old baby (very sleep-deprived).

b) Ironically, it was so densely interesting and full of helpful insight I felt like I couldn’t take it in large doses (I needed time to digest and act upon what I’d learned before continuing).

Although most people have not read it in its entirety, it has significantly impacted market research and wider society since its publication.

What is behavioral science, and why is it important for market research?

A succinct explanation for behavioral science is that it ‘encompasses a multidisciplinary approach, integrating insights from psychology, economics, sociology, and cognitive science to understand how individuals make decisions.’

Behavioral science acknowledges the role of cognitive biases, emotions, and social factors in human decision-making. This sharply contrasts with the classical economics portrait known as “Economic man” (Homo economicus), accredited to economist Adam Smith. The economic man theory assumes that humans “act rationally and with complete knowledge, and seek to maximize personal utility or satisfaction.”

Market research has traditionally relied on surveys, focus groups, and other methods to collect data. These methods rely on people saying what they think, what they like, or don’t like, and what individuals believe they might do (or not do) in a given situation.

Before behavioral science became mainstream, it was generally thought that people’s actions and beliefs were congruent, when in reality, this doesn’t always play out.

However, market researchers generally lacked the language or framework to describe this discrepancy (coined the intention-action or belief-action gap) let alone how to predict it or use it to an advantage.

Enter behavioral science, introducing a more nuanced understanding of consumer decision-making and, perhaps most importantly, a framework and series of rules that made interpreting behavior more scientific and criteria-based.

What these books discuss and how they apply to market research and insight:

In his book Nudge, Thaler introduced the concept of ‘nudging’—subtle behavioral interventions that guide individuals toward making better choices without restricting their freedom.

Nudges take advantage of cognitive biases to encourage or discourage behaviors.

These include concepts like

Choice architecture—Influencing people’s behavior simply by changing how options are presented to them. For instance, imagine an online shop that, by default, highlights environmentally friendly and sustainable products at the top of the search results.

Loss aversion—Feeling the pain of losses more severely, especially monetary, than corresponding gains or wins. For example, declining to sell a stock that has decreased in value for fear of realizing a loss, even though it might be a rational decision based on market conditions.

Status quo bias—The tendency to accept what already exists. People often ‘choose’ the default setting for a product or service, especially if it has a low immediate impact on their day-to-day lives. Some defaults automatically grant app permissions, requiring users to opt-out if they want restrictions. Others default to denying permissions, prompting users to opt-in. The default can nudge users towards more permissive sharing or stricter privacy, depending on their choices.

Thaler's work profoundly impacted market research by encouraging researchers to shift from simply describing what behaviors were happening to more predictive, prescriptive models explaining why it happened:

Outlook before:

“In this instance, people appear to be acting irrationally or in a contradictory fashion.” “Isn't that confusing? Well, people are just like that, right?”

Outlook after:

“People behave this way in these instances and circumstances because of fundamental, predictable cognitive biases grounded in human physiology and psychology.”

By understanding, capturing, and systematically describing these features of human behavior, behavioral science has enabled marketers to design interventions that resonate more with consumers psychologically.

An intervention is distinguishable from a nudge by being more comprehensive. Suppose a company sells fitness trackers—instead of just using nudges like reminders or positive reinforcement, marketing insights could guide a behavioral science intervention by offering personalized feedback and goal-setting features to help set realistic and achievable goals.

Thinking, Fast and Slow: dual systems of thought.

The book I mentioned earlier, Thinking, Fast and Slow, introduces the idea of people having two systems of thought. Kahneman labeled them System 1: the fast and intuitive system, and System 2: your slow and analytical system.

System 1 (Fast) thinking relies on heuristics and operates effortlessly, allowing individuals to make quick decisions based on intuition and past experiences—like your gut or knee-jerk reaction to something.

System 2 (Slow) thinking, conversely, claims that thinking involves deliberate reasoning, requiring more cognitive effort and attention. You focus on the situation or question and dedicate mental resources to coming up with a considered response or answer.

Market researchers have always distinguished between consumers' spontaneous vs. considered reactions to a product or idea. This differentiation arguably explains these behaviors even before Kahneman conceived of his systems. For instance, in an ad test, the immediate (spontaneous) reaction to an ad is far more important than how participants deconstruct or rationalize it after considering it.

However, Thinking: Fast and Slow helped create a consistent, scientifically supported framework for consumer behavior and decision-making, allowing researchers and marketers to design their approaches consistently and in an informed way.

How is behavioral science leveraged in marketing and market research?

Since behavioral science became mainstream, we now understand why certain techniques work and can deliberately apply them in various marketing and research situations with heightened precision:

Cognitive biases and decision-making

Behavioral science highlights numerous cognitive biases that influence decision-making.

For example, the anchoring effect can be leveraged in pricing strategies and marketing communication, where individuals rely heavily on the first piece of information encountered.

A tried and tested retailer strategy is to provide a cost anchor in the form of a regular retail price, followed up with a limited-time discounted price, usually in a different color and large font. Consumers can be convinced they are receiving a substantial discount, based on providing an original (higher) ‘anchor’ price for consumers to compare to—even if rationally they are aware of what the retailer is doing!

Market researchers can use experimental design to understand how these biases affect consumer choices in various contexts, for example, testing the order effect of different product prices when presented in physical or virtual stores and how it impacts consumers’ propensities to purchase.

Loss aversion and marketing strategies

Thaler's concept of loss aversion, the tendency to avoid losses over acquiring equivalent gains, has significant implications for marketing.

The following techniques play right into human loss avoidance cognitive bias. They can subtly pressure individuals into purchasing when they otherwise might have delayed or avoided it altogether:

Framing messages regarding potential losses or emphasizing the fear of missing out (FOMO)

Putting a ‘limited-time offer’ or having a timer counting down when buying event tickets.

An accommodation site informs you that ‘3 other guests are looking at the room you’re trying to book.’

Nudging for positive outcomes:

Thaler’s nudging concept has found applications in marketing and consumer behavior. Nudges are designed to influence behavior but not in a way that is overt enough to annoy the person being nudged (so much so that they resist or resent the intervention).

Nudges might ensure the order in which food in school cafeterias is presented begins with healthier options earlier, with less healthy options later.

My local Chinese restaurant does this but focuses on ingredient cost rather than most vs. least healthful options. The all-you-can-eat buffet is set up to present the filling, inexpensive options (rice and noodles) at the start and the most expensive items (chicken wings, prawns) at the end.

Nudges can have a subtle yet powerful effect. A good example is when patients schedule appointments with their doctor. The receptionist can ask them to repeat the date and time of the appointment and confirm their intention to attend. This simple nudge effectively reduces the chances of them missing the appointment. Having people state their intended action aloud encourages them to avoid the cognitive dissonance of contradicting themselves by not attending the appointment in the future.

Case studies and real-world applications of behavioral science

These real-life examples offer a glimpse of the transformative power of behavioral science in diverse contexts:

Amazon's one-click ordering

Amazon's implementation of one-click ordering is an excellent example of designing a process that considers fundamental human biases (though it wasn’t necessarily designed in response to Kahneman’s work). By reducing the friction in the purchasing process, Amazon taps into System 1 cognitive biases, making it super fast and easy for consumers to make impulsive buying decisions. This approach not only enhances user experience but also increases sales.

Default options in pensions and retirement plans

Thaler's work around choice architecture and understanding cognitive biases such as hyperbolic discounting, where people place more importance on their immediate needs over those they might have in the future, has influenced policies related to retirement savings.

Companies take advantage of cognitive inertia in the form of status quo bias by making enrollment in retirement plans the default option for employees (opt-out rather than opt-in). This cognitive bias refers to when people prefer that things remain the same and accept an existing situation. A simple change like this, which aligns with people’s behavioral biases, can have significant, positive implications for individuals' long-term financial well-being.

Uber's surge pricing

Uber's use of surge pricing during peak demand is a strategic application of the anchoring effect discussed earlier. Uber establishes a reference point for consumers by presenting higher prices during busy times. While this may initially seem disadvantageous—the anchoring effect can increase perceived value during non-peak times, when prices return to normal: “Oh, the price is quite cheap now relative to earlier.”

Challenges and ethical considerations

Behavioral science has undeniably positively impacted the field of market research. However, it also poses specific difficulties and ethical concerns. Marketing and research strategies that may be perceived as manipulating consumer behavior can create doubts about informed consent. As we work toward achieving successful outcomes, we must respect consumers' autonomy while using our understanding of human behavior. Transparency is key. We must openly share our methods and goals with consumers and ensure they fully understand what they're agreeing to.

Where next for behavioral science and market research?

Integrating behavioral science into market research and consumer insights has transformed how businesses understand and interact with their target audiences. Richard Thaler's contributions to behavioral economics, along with Daniel Kahneman's dual-system framework, have provided incredibly valuable tools and frameworks for exploring and systematizing the intricacies of human decision-making.

By acknowledging the influence of cognitive biases, emotions, and dual systems of thought, marketers and market researchers can design more effective strategies that resonate with consumers on a deeper, behavioral level.

As we continue to delve into the complexities of human behavior, the synergy between behavioral science and market research will undoubtedly pave the way for strategies that bridge the gap between consumer preferences and business objectives. Embracing behavioral science principles allows businesses to not only understand why consumers make certain choices but also to influence those choices in an ethical, sustainable, and mutually beneficial way.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?