Selling software in the era of the end user

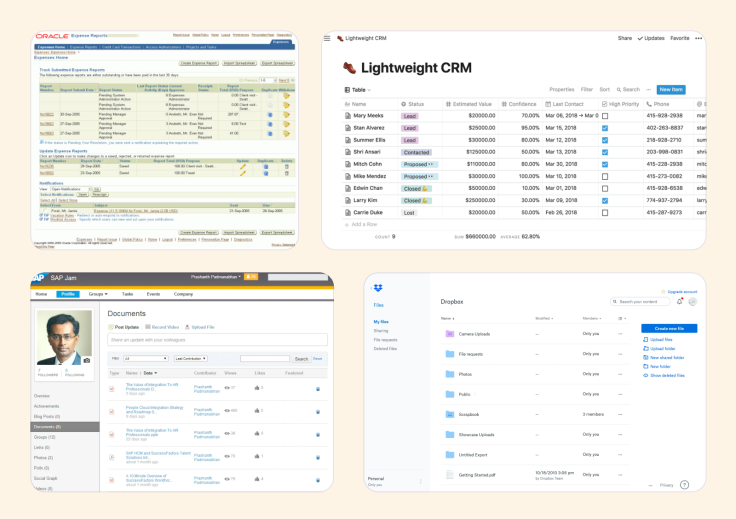

Over the past couple decades, the consumerization of enterprise software has produced a new breed of vendors who have quickly supplanted their traditional counterparts. In the early days, pioneers in the field like Oracle and SAP would sell software to a small number of IT managers or executives, who had little consideration for the user experience of the end users who would have to use such software. This software was expensive to build and buy, had involved lengthy sales cycles, and the end users had no say in their use of the software.

Today, a new class of software has emerged, championed by companies like Slack, Dropbox, Airtable, and more recently Notion. These products have adopted the user experience patterns and qualities pioneered in consumer software developed by Apple and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. We’ve seen concepts born in the consumer space, such as emojis, reactions, and hashtags, as well as the viral loops these platforms employ to keep their users engaged, make their way into business software.

Executives in this new breed of company have moved away from revenue to report active usage, just like their consumer counterparts. The newfound familiarity and intuitiveness of business software has meant that buyers now spend less time and energy on training and onboarding. Instead of IT managers and executives pushing software from the top down, end users are now demanding that enterprises adopt this new class of software to help them be more effective in their roles. This entire motion is driven by the quality, intuitiveness, and consumer-appeal of the software.

This shift has been a boon for user experience and design practitioners. When I started out my career in product design, the transition towards a consumer-standard for business software was starting to manifest in design circles. While working at Atlassian, the organization commenced a multi-year journey to transform their core business of on-premise software, usually deployed and managed by an IT admin, to a cloud-first platform that could be tried and adopted by anyone. The bet was to expand beyond the technical base of developers where Atlassian had seen initial adoption, to non-technical teams across marketing, legal, and operations.

To support this, Jira—a decade-old tool lovingly reviled by many—was undergoing a radical redesign, leveraging many elements found in consumer software, to make itself more approachable and appealing for the masses. This quest also saw the $425M acquisition of Trello, a tool that had fully embraced consumerization. In Trello, a playful illustrated mascot of the co-founder’s Siberian Husky, named Taco, follows you around the product as you decorate your kanban board with illustrated stickers, GIFs, and photos—something that would be at home on Facebook or Instagram, but totally unknown to conventional business software.

I later went on to join Intercom, a company which had grown up in this consumerized world. They were increasingly becoming industry-recognized as they deployed design and user experience to aggressively land emerging startups and challenge incumbents like Zendesk and HubSpot. Intercom had effectively transformed the cold, robotic, and impersonal experiences of live chat and customer support into a more authentic and personal experience that delivered on newly raised user expectations.

Others took note and new startups were seemingly popping up every other week with inspired takes on the live chat category. Live chat had effectively become commoditized as everyone sought to replicate this new customer standard. Meanwhile, Intercom was scaling up sales, moving upmarket, and revising pricing and packaging in a bid to fuel continued growth. Intercom was starting to lose its shine in the industry as it lost out to startups who pursued aggressive freemium pricing and go-to-market motions, and to new entrants such as Drift who focused exclusively on the live chat for sales category.

With end users now more empowered than ever to influence and decide the software they use day-to-day, their consumer expectations have naturally translated into how they expect to try and buy business software. In recent years, this buying motion has been heralded as product-led growth, or ‘PLG’. Championed largely by the venture community and the folks at OpenView who have dubbed this the “end user era”, PLG describes a distribution model that is focused on solving end user challenges, with the elimination of any friction for these users to get value from the product as quickly as possible.

Practically what this translates to for most PLG models is an effortless free trial or free offering, transparent and clear pricing, intuitive onboarding and a clear path to value, a self-service support experience backed by a community of users, and an ecommerce checkout flow with no sales conversation. These PLG tactics were pioneered by Atlassian early on to drive adoption among developers, famously with no sales team (but don’t believe what you read; Atlassian does now have a sales team). Atlassian’s recent investments in the consumer experience should be seen as a doubling down of the ingredients that saw initial success with developers to other non-technical markets. In fact, this trend was called out in Atlassian’s S-1 filing at IPO:

Following the “bring your own device” trend, employees are increasingly empowered to “bring your own software”, leading to the user-driven viral adoption of new types of consumer-style software products within an organization.

For Intercom, despite having the qualities of a consumer experience, the shift to move more upmarket, with increased focus on sales and opaque pricing translated into additional friction for buyers and created a vacuum for challengers to emerge with more aggressive self-service go-to-market motions that fully embraced the principles of PLG. I reflect on my two experiences at Atlassian and Intercom to emphasize that it simply isn’t enough to build a consumer-grade experience, the way that product is sold and distributed needs to also match consumer expectations to properly embark on a successful PLG motion.

This PLG motion is what we’re seeing play out here at Dovetail. Our customers are experienced user researchers and user experience practitioners—how they do their work, and the tools and processes they employ is entirely in their purview. They’re not experienced software buyers or procurement professionals, they’re just looking for a tool to help them be more effective in their role. Our customers will sign up for a free trial, give Dovetail a go, and see if they find value. This all happens without a sales conversation; no barriers to starting a trial, no lead capture forms, and no “talk to sales” or “book a demo” prompts. Customers will make the decision to try and buy Dovetail entirely without us.

So where does that leave the sales function at Dovetail? More often than not, those looking to buy Dovetail often work in enterprise organizations and Fortune 500 companies. These individuals are experienced in their craft and can effectively evaluate whether Dovetail meets their needs, but they’re inexperienced in navigating the complexity and bureaucracy of purchasing software within their organization. The organizations have complex procurement processes that might involve proof of concepts, wider stakeholder buy-in, detailed security and risk assessments, and complex contracting discussions with their legal and sourcing departments. The intent of these individuals is to introduce new transformational software into their organization, and instead they find themselves running the gauntlet through their internal organizational process.

At Dovetail, we’ve seen that the majority of our “selling” effort, if you could call it that, is spent equipping these informed—but unsophisticated—buyers with the tools and materials to help them navigate the complexities and red tape of purchasing software in their organizations. Instead of pitching to uninformed customers and convincing them to sign up, we focus on understanding what our prospective customers’ purchasing process looks like, and how we can best support them through it. In effect, the ‘sales team’ at Dovetail act as consultative partners who are working to accelerate the bottom-up self-service adoption within complex enterprise purchasing environments. Once we land a customer, and as a customer uncovers more value over time and continues to grow with us, any subsequent conversations concerning expansion are efficient and painless both for the customer and for our sales team.

In my next article, I’ll share and unpack some of the tactical activities and strategies we’re employing to help support our prospective customers on this journey to adopt Dovetail within their organization.