What is grounded theory? Finding insights in qualitative research

Let’s role-play for a minute

Imagine with me—it’s your first day on the job as a UX designer in a completely new industry. You have your shiny new computer, your LinkedIn is updated, and you’re ready to shake things up.

"Welcome aboard," says the friendly product manager, "Hope you’re ready to roll up your sleeves and disrupt the industry. Let me know if you have any questions before we get started. Oh, and by the way, we have more than 20 engineers waiting for your designs for this upcoming sprint, but no rush..."

(Gulp)

Chances are if you’re reading this you’ve experienced a similar situation before. As UX designers, our job is to bridge the needs of our users and the business to create the best experience for both. But how do we do that when we’re starting from scratch and know very little about the domain we’re entering? Who are our users? What are their problems? What are their goals?

Abraham Lincoln says it best:

If I only had an hour to chop down a tree, I would spend the first 45 minutes sharpening my axe.

In this case, UX Research is our axe and the tree is our user experience—the better we understand our users and their problems, the easier it will be to address and anticipate their needs. With this, every great product starts with excellent research.

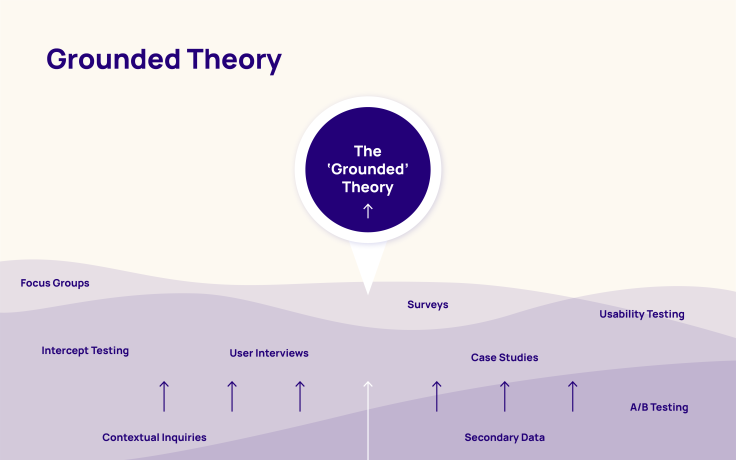

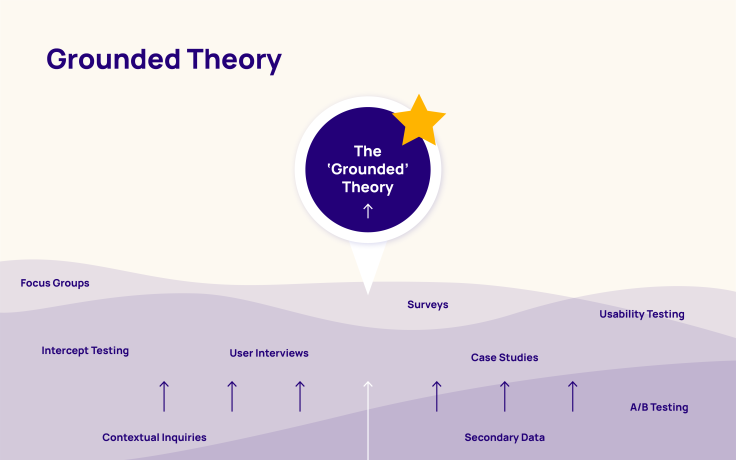

With UX, there are dozens of research methods for discovery, testing, and validation—but what’s the right methodology (i.e., evaluative, generative, explorative, quantitative, qualitative, etc.) to drive our research method selection? In our case, when you’re in a new domain building out foundational research or looking to gather large amounts of raw data from several data sources, one methodology always sticks out —Grounded Theory.

I stumbled across GT nearly four years ago when I was running a research discovery effort for a large fortune 100 client that needed to “start over.” Their previous research had gone stale and they were losing touch with their users and what problems to solve. I figured GT, with its simple bottom-up approach to data-driven theory generation, would be the perfect methodology for the project.

Hopefully, in this article, you’ll see how Grounded Theory can help you build data-driven theories about your users, their environment, and the phenomena (an observable fact or event) as a whole to inform your customer understandings and design decisions moving forward.

What is grounded theory?

Whether you’re aware of it or not, you’ve most likely used Grounded theory methodology and methods in your day-to-day UX practices. When attempting to generate theories from your qualitative research data, GT is widely seen as the “go-to” methodology. Since its inception nearly five decades ago by two sociologists Glaser and Strauss, GT has spread from sociology to other social sciences and fields of study, such as public health, education, business management, and now user experience research.

'The discovery of theory from data systematically obtained from social research' (Glaser and Strauss 1967)

The purpose of GT is to generate theories that emerge from or are ”grounded” in data. It is used to uncover learnings around processes, social relationships, and behaviors of groups.

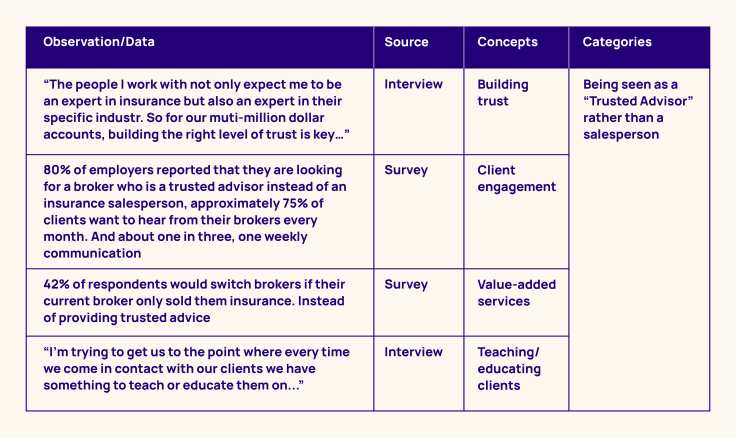

For example, I work in the insurance industry. When I first entered the industry, I figured price was the driving component behind a business owner’s purchasing behavior. However, after several rounds of interviews, I learned the relationship with the insurance agent is orders of magnitude more important, since the business owner needs to have “peace of mind” that their business is insured appropriately. They wanted a “trusted advisor”, not just an affordable insurance policy.

With GT, we’re tasked with the goal of finding patterns and categories that might emerge from the data rather than making assumptions (“insurance buyers just want the cheapest policy”). The theory needs to be “grounded” in the data, hence “Grounded Theory”.

So then, what is considered “data”? Really anything that comes out of a research method (quantitative or qualitative) should be considered data when developing your theories. Primarily, you’ll want your theories steeped in first-party data (from your interviews, feedback sessions, etc.) but feel free to harden your theories with even third-party data like whitepapers or academic resources.

When to use grounded theory

When you need to familiarize yourself with a new domain or topic and you want to be close to the data

When there is a lack of existing theories or research available

If you’re looking to create theories or insights with a mixed-methods approach (qual/quant)

When collecting a large amount of data

Benefits of grounded theory

Great for new projects where discovery and exploratory methods are needed

Produces large amounts of data

Provides a “fresh” perspective on deep and rich data surrounding a given research topic

Helps reduce confirmation bias since everything is rooted in data

Once a researcher/designer has a nuanced level of understanding on a topic, they’re enabled to think divergently and creatively

GT is very flexible and the methods employed can change as the research study progresses

If adopted across the organization, GT supports a structured approach to data analysis

Observations/findings are easily traceable and tightly connected to the source data

Limitations of grounded theory

The process of GT is extremely time consuming and can be difficult to do consistently as more and more data comes in

The methods for data collection and analysis take skill and proper training to perform

With large amounts of data in hand, it can pose problems to manage and analyze consistently

Each research topic has no guaranteed start/end date

Difficulty recruiting for ongoing research

Grounded theory approach

When it comes to GT, a researcher does not just begin with a theory and set out to prove it. Rather, a researcher begins with an area of study and allows relevant data to emerge.

As with most research efforts, GT starts off with a research question—this question helps define the scope (who to talk to and what to ask about) and strategy (what methods to use) around the research topic.

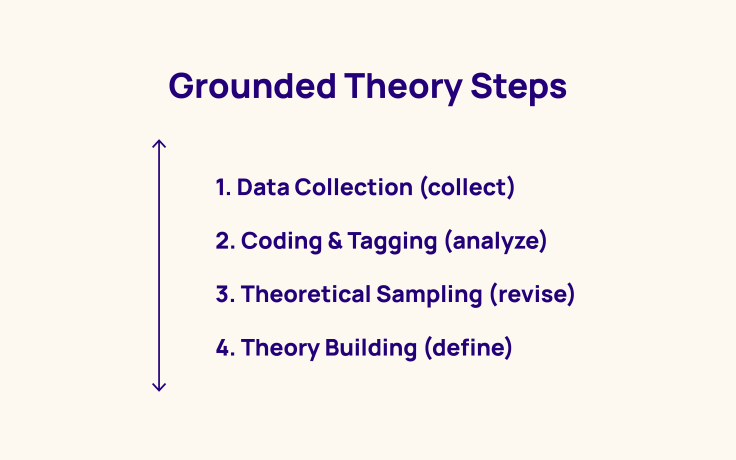

Grounded theory steps

Data Collection

In grounded theory, data collection is exactly the same as traditional qualitative research methods and typically begins with a research question.

After a research question/area of interest has been identified, it’s important to begin your research by taking a few steps back and starting with very broad concepts, more general in your thinking.

Additionally, if you’re familiar with the topic at hand it’s equally important to remove biases and assumptions. To do this effectively, try to adjust your worldview and remove any existing theories you might have so you can evaluate the data with a fresh perspective and allow the world to teach you the words, phrases, and idioms while you’re studying and observing so you can ask the “dumb questions” (“what does that mean? Can you explain…?, etc.”).

Remember, “all is data” so get creative with what data you collect and how.

Sample list of data collection methods

Recorded in-depth interviews

Observational methods

Focus groups

Surveys

In-app feedback tools

Customer advisory boards

Product analytics

Note-taking

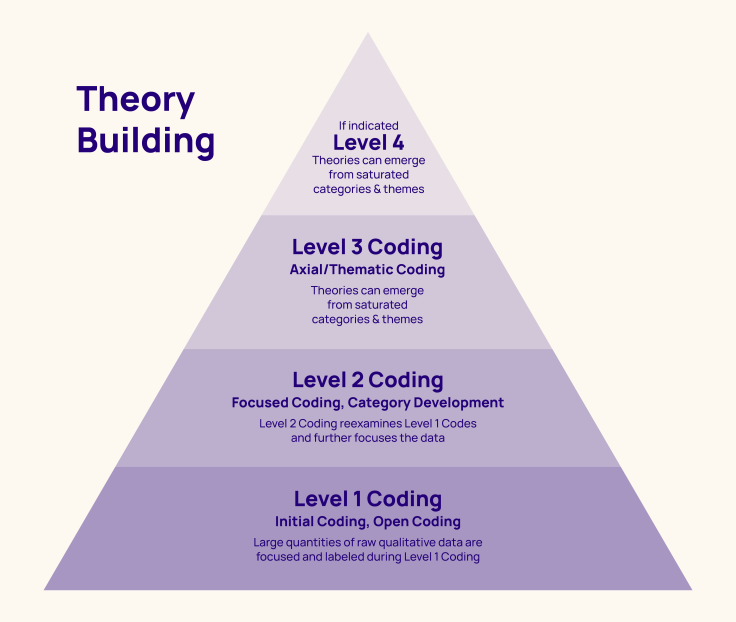

Coding and Tagging (analysis)

Coding (and tagging) can simply be defined as the process of breaking down your data and organizing them by codes (or labels) so you can identify themes and causal relationships between disparate points.

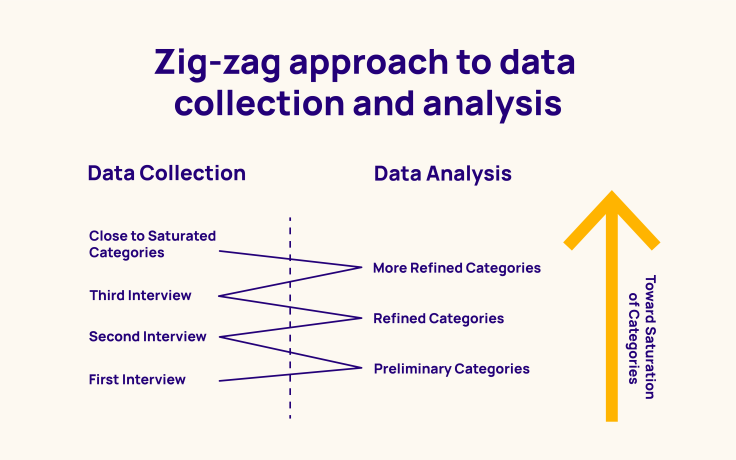

By its nature, the process of data collection and analysis in grounded theory is quite flexible and can often be done simultaneously. This type of back and forth is called the “zig-zag approach” to collection and analysis where the researcher is continuously refining their “concepts” and “categories” (we’ll define these in a second) on the subject until there is diminishing returns or “theoretical saturation” (when new data comes in and does not lead to refinement of thinking or new ideas).

**Aside**

When in the data collection phase, thematic analysis tends to go hand-in-hand with grounded theory and is one of my personal favorites when analyzing large amounts of data and setting up a proper UX repository (especially in Dovetail)!

**End Aside**

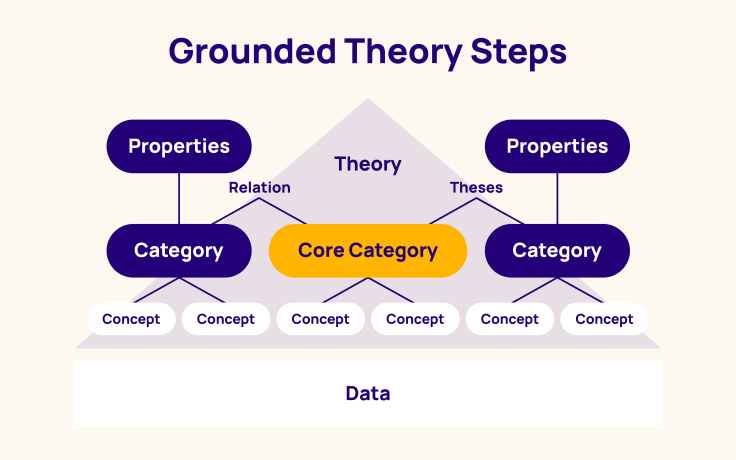

When analyzing your data, we need to somehow deconstruct it so we can reassemble it into actionable information or findings—we do this by evaluating our data and organizing our findings into concepts and categories.

“Concepts” are your low-level codes, or put simply, the first layer of data you highlight/ tag that you found important. I once asked my mentor—“what should I code?” and she said, “code and tag anything that you might find interesting and that you might want to share with me if we bumped into each other in the hallway...”.

It’s quite simple. Anything that you find interesting is meaningful—tag it!

That’s “concepts” in GT.

Now, “categories” are clustered concepts that have similar ideas (and can come from several data sources). Typically, these are written in the form of insights or themes in my experience.

A key method that’s used in grounded theory is called the “constant comparative” method, which means any findings (concepts, categories, theories, etc.) are constantly compared against each other as new data emerges in order to further refine your interpretations and theories.

Revising data collection methods through theoretical sampling

As with any process of analysis, it’s important to look back and course-correct. How are things going? Are we learning anything new? Are we surprised by the new data coming in or are we receiving similar answers? Are the existing categories and concepts abundantly supported?

In grounded theory, Glaser and Strauss call this process “theoretical sampling”, and it's a way for researchers to identify a category that might need further research and inquiry.

Glaser and Strauss on theoretical sampling:

“The process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes, and analyzes his data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them” — Glaser and Strauss (1967)

As you review your concepts and categories over time, your existing research should help direct (or redirect) you as to where to go and what data to collect next.

But how do researchers know when to stop collecting data?

Strauss calls this moment “theoretical saturation.”

“Theoretical saturation: The point in category development at which no new properties, dimensions, or relationships emerge during analysis”

So when the concepts and categories are theoretically saturated and no new concepts are emerging from the data!

Theory Building

Lastly and most importantly, in order to identify a theory that has emerged from the data, you have to have a deep and nuanced understanding of it—Glaser and Strauss call this “theoretical sensitivity.”

Theoretical sensitivity simply means that through the ongoing process of data collection, analysis, and even more collection, researchers become more familiar with the data and are able to unearth insights and evaluate relationships between concepts and categories that lead to relevant theories (or insights).

In grounded theory, most of these theories come from identified categories which are also referred to as “core categories.”

In my experience, writing theories are not as actionable for our needs in the user experience space, therefore, I’ve found that writing your learnings as one of the following can be helpful:

Insight statement

Problem statement

Job-To-Be-Done

Wrapping Up

Wrangling research data and developing theories surrounding your topic can be overwhelming and difficult. As a researcher who also designs, I’m all for making things easier.

Use GT to organize your data and consistently groom it for structured, deliberate, and insightful theories/learnings. The consistency, clearly defined and organized concepts and categories will help you over the long run! Additionally, as a design manager (who’s currently hiring wink wink) it’s important to have a consistent process among our UX teams when it comes to data collection and analysis, so when we scale our research efforts, we’re not left with a dumping ground of raw data, rather clearly defined piles of dynamite insights!

So the next time you’re poised with a discovery project or enter a new job in a new industry, give Grounded Theory a try and watch the learnings pile up!

This article covers the very basics of grounded theory, if you’re interested in learning more please check out my full course on UX research and a few of my favorite books. You can also reach out to me any time via LinkedIn.

Written by Brennan Martin, User Experience Lead, Manager, Acrisure. Brennan is a UX designer and researcher with over eight years of experience. He’s worked on various mobile and web applications ranging from enterprise B2B to B2B2C and B2C experiences. He’s known for his strong sense of storytelling and his fearless advocacy for his users and their needs. Brennan’s pathfinding in uncertain situations is well tested and highly structured—with his years of experience leading UX strategy, design thinking workshops and driving Atomic UX Research best practices in large organizations, he seeks to deliver high quality insights with measurable impact. When he’s not out in the field researching or testing new designs, you can find him trying out new restaurants with his wife, hiking the amazing national parks all over the US, or mentoring budding designers though one of his UX research courses.